Written by Harini Sivanandh Ramadass | Art by Harini Sivanandh Ramadass

Riboflavin, also known as vitamin B2, is an essential nutrient crucial for various physiological processes in the human body. Its deficiency, termed riboflavin deficiency or ariboflavinosis, can lead to significant health complications. This passage aims to delve into the causes, symptoms, and management strategies associated with riboflavin deficiency, shedding light on its importance in maintaining overall health and well-being.

Riboflavin deficiency can arise from multiple factors, with inadequate dietary intake being a primary cause. Since the human body does not store riboflavin in large amounts, continuous dietary intake is essential to prevent deficiency. Malabsorption disorders, certain medications, alcoholism, and increased physiological demands such as pregnancy or lactation can also contribute to riboflavin deficiency. These factors disrupt the body’s ability to absorb and utilize riboflavin efficiently, leading to its deficiency over time.

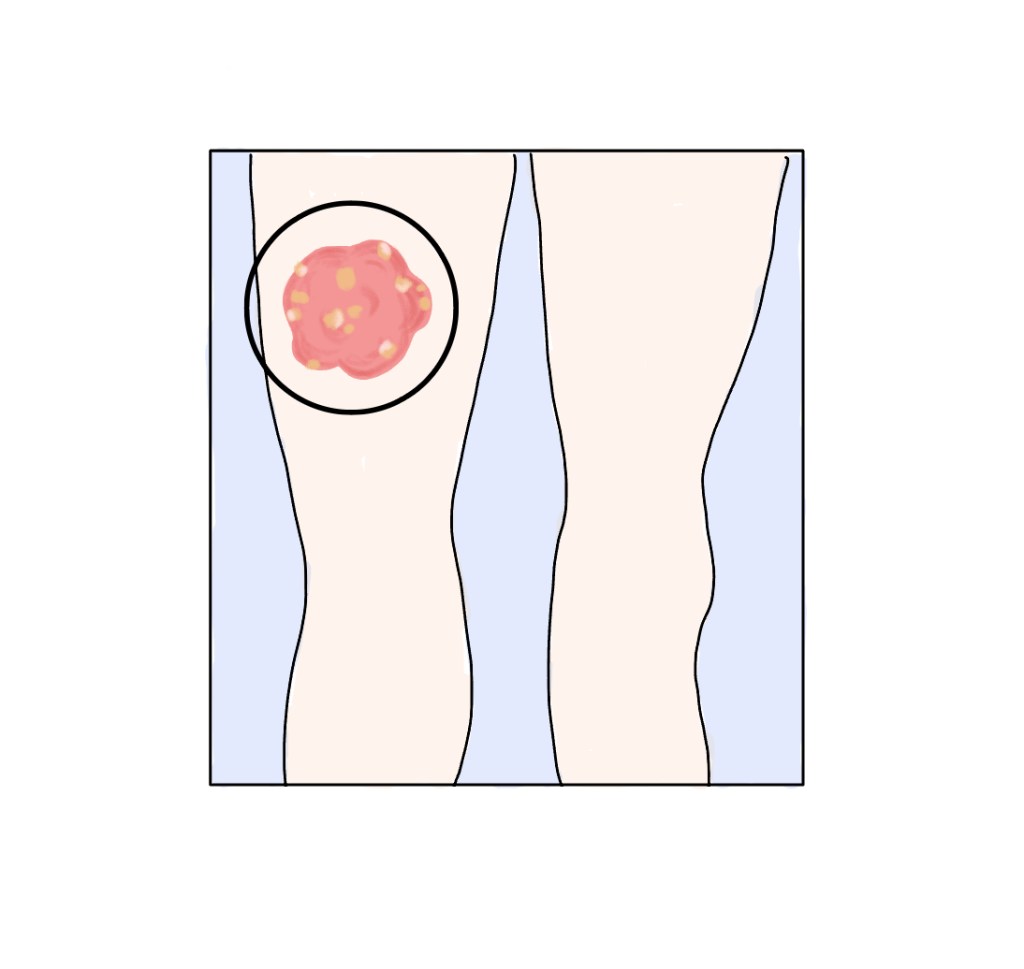

The symptoms of riboflavin deficiency can manifest in various ways, affecting different systems of the body. One common manifestation is the inflammation and discomfort of the mouth and throat, with symptoms such as sore throat, cheilosis (redness and swelling of the lining of the mouth and throat), angular stomatitis (cracks or sores at the corners of the mouth), and glossitis (inflammation of the tongue). Skin disorders, anemia, and eye-related issues like photophobia and blurred vision are also prevalent symptoms of riboflavin deficiency. Severe deficiency can even lead to neurological complications, highlighting the critical role of riboflavin in maintaining proper bodily functions.

The management of riboflavin deficiency involves addressing the underlying causes and ensuring an adequate intake of riboflavin-rich foods or supplements. Healthcare professionals play a crucial role in diagnosing and treating riboflavin deficiency effectively. They may recommend dietary modifications to include foods rich in riboflavin, such as dairy products, lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, green leafy vegetables, and fortified cereals. In cases of malabsorption disorders or other medical conditions hindering proper absorption, supplementation may be necessary under medical supervision. However, it’s imperative to consult a healthcare professional before initiating any supplementation regimen to prevent potential adverse effects.

In conclusion, riboflavin deficiency poses a significant health risk and can lead to various complications if left untreated. Understanding the causes, symptoms, and management strategies associated with riboflavin deficiency is crucial for healthcare professionals to provide effective care for affected individuals. Adequate intake of riboflavin through diet or supplementation, along with addressing underlying medical conditions, is essential for preventing and managing riboflavin deficiency and maintaining overall health and well-being. It is important to address issues circulating deficiencies surrounding malnutrition to educate the general public to have balanced meals to remain healthy.

Works Cited

Powers, H. J. “Riboflavin (vitamin B-2) and health.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 77, no. 6, 2003, pp. 1352–1360. PubMed, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20499043/#:~:text=Abstract,to%20the%20rarest%20human%20disorders.

Traber, Maret G., and W. Douglas Ayres. “Therapeutic efficacy of high-dose riboflavin in two patients with Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere syndrome.” Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, vol. 36, no. 6, 2013, pp. 1095–1100. ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002916523057945.

National Institutes of Health. “Riboflavin: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals.” Office of Dietary Supplements, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Riboflavin-HealthProfessional/.

Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline. “Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline.” National Academies Press (US), 1998, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1181951/.

Scriver, Charles R., et al., editors. “Riboflavin Responsive Disorders.” The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease, McGraw-Hill Education, 2019, https://ommbid.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookId=2709§ionId=225081431.

Leave a comment