Written by Kirsten Batitay | Art by Anoushka Pandya

Despite being a rare, neurodegenerative disorder affecting 1 in 10,000 people in Western countries, Huntington’s Disease guarantees the death of whoever is affected by it. This inherited disorder causes nerve cells in parts of the brain, mainly the basal ganglia, to deteriorate and die gradually. However, it is not evident at birth, and symptoms usually begin to present themselves in middle-aged people, though Juvenile HD can, on rare occasions, affect teenagers and children. From then on, those affected have a life expectancy of 10-25 years.

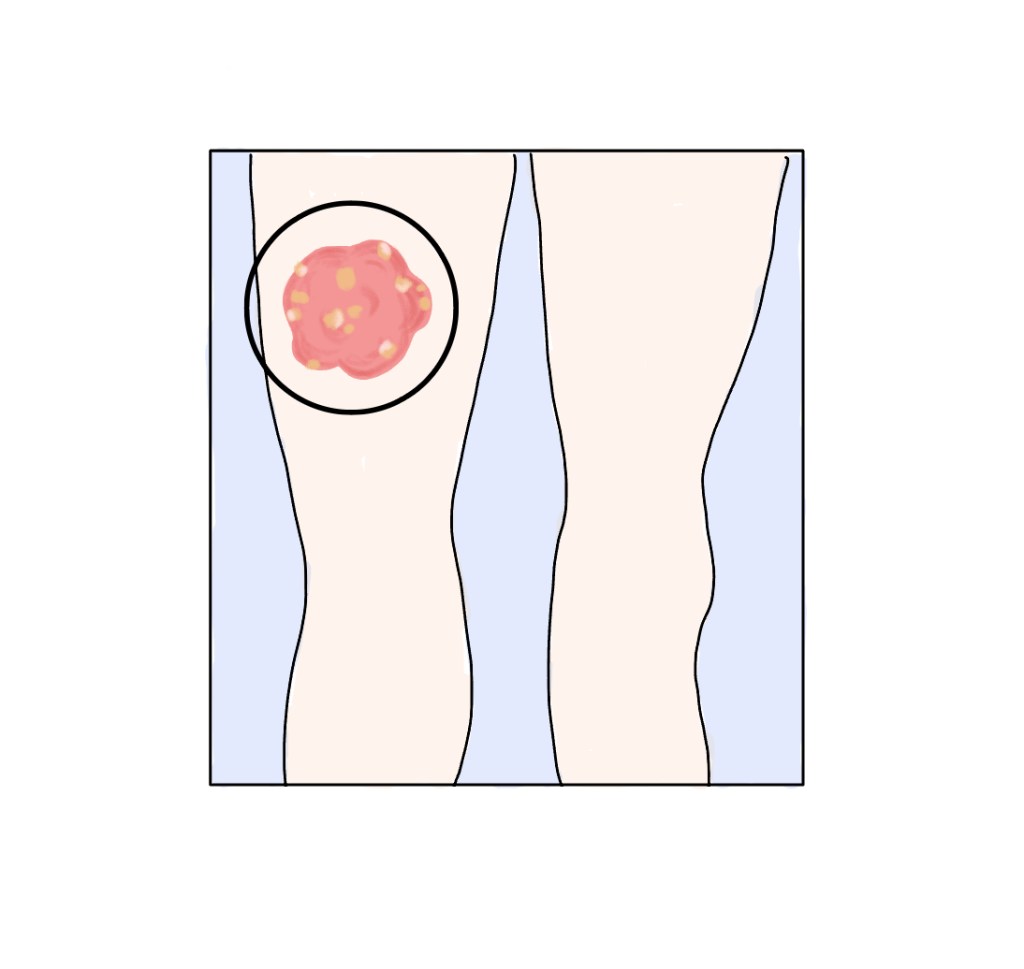

The early signs of HD may include clumsiness, balance and movement issues, and behavioral changes that devolve into worse symptoms. Because the basal ganglia is the part of the brain that controls movement and is responsible for organizing and managing thoughts and emotions, those with this disease develop uncontrollable muscle movements, otherwise known as chorea. Other physical changes include tremors, unusual movements of the eye, slurred speech, weight loss, and seizures, which can culminate in the affected being required to stay in bed or a wheelchair.

In addition to these detrimental physical changes, cognitive changes include problems with attention span, memory, and judgment and having difficulty in problem-solving, decision-making, or learning new things. These progressions thus render the affected unable to walk, drive, or care for themselves. Other such changes in behavior include mood swings, social withdrawal, depression, anxiety, or the development of other disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder, mania, and bipolar disorder.

How, then, does this devastating disorder come to be? Fundamentally, Huntington’s Disease occurs due to a defective gene on chromosome 4, which causes an excess build-up of the toxic Huntingtin protein. Those with HD may also have 36 or more repetitions of the DNA bases, cytosine, adenine, and guanine in this gene, whereas normal people usually have around 20-25. But as HD is inherited, each child of a parent who has it has a 50% chance of inheriting the affected chromosome 4.

Being a disease with symptoms that usually start showing later in life, HD can be diagnosed using neurological exams, knowledge of family history, diagnostic imaging, and genetic tests. These procedures test functions like movement which are affected by HD, use CT and MRI scans to see parts of the brain that are damaged, and count repeats of the CAG bases.

Due to its nature, Huntington’s Disease currently has no cure, so symptomatic treatments are used. These include using tetrabenazine to treat chorea, antipsychotic drugs to target hallucinations or violent outbursts, and drugs for depression and anxiety. Despite the lack of a cure, research is being conducted by scientists to find treatments for HD. A few examples include using biomarkers to predict, diagnose, and monitor it, using cell lines to understand neuron malfunction and death, testing new drugs, and using gene-editing in cells or animals to understand how to stop the production of the Huntingtin protein in certain locations or amounts.

Huntington’s Disease has long been a cause for concern in families, especially when it is taken into consideration the inevitable deterioration in health one will experience once symptoms begin to show. It is for this reason that those with a family history of it may choose not to get tested, or couples in which one partner has it may choose not to have a child and instead resort to other methods of having one.

Although losing hope can be the simplest reaction to this disease, there are still ways to help those with HD. The most important thing is to educate ourselves on it and what being afflicted by it entails. For those of us who may have a loved one affected by it, we must stay by their side, helping them find support groups and physicians or even assisting them with tasks they can no longer perform. Sometimes doing seemingly simple things can go a long way, and especially with the research being conducted, it is imperative that we not lose hope when it comes to Huntington’s Disease.

Works Cited:

“Huntington’s Disease.” National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, http://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/huntingtons-disease#toc-what-is-huntington-s-disease-. Accessed 30 Mar. 2024.

“Huntington’s Disease.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 17 May 2022, http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/huntingtons-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20356117#:~:text=Overview,(cognitive)%20and%20psychiatric%20disorders.

“What Is Huntington’s Disease?” Huntingtons, 27 June 2017, huntingtonsqld.org.au/huntingtons-disease/what-is-hd/#:~:text=There%20is%20currently%20no%20cure,is%20not%20evident%20at%20birth.

Liou, Stephanie. “My Friend Has Huntington’s Disease – How Can I Help?” HOPES Huntington’s Disease, 6 Sept. 2016, hopes.stanford.edu/my-friend-has-huntingtons-disease-how-can-i-help/.

Leave a comment