Written by Micaela Montinola | Art by Nourah Bakary

Immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that essentially taps into our own immune system’s potential to fight cancer. Our immune system is the complex network of tissues, organs, and white blood cells that work together to help our body fight off infections and diseases in a highly specific manner. Utilizing immunotherapy to treat cancer could result in fewer side effects and more potential for long-lasting benefits post-treatment.

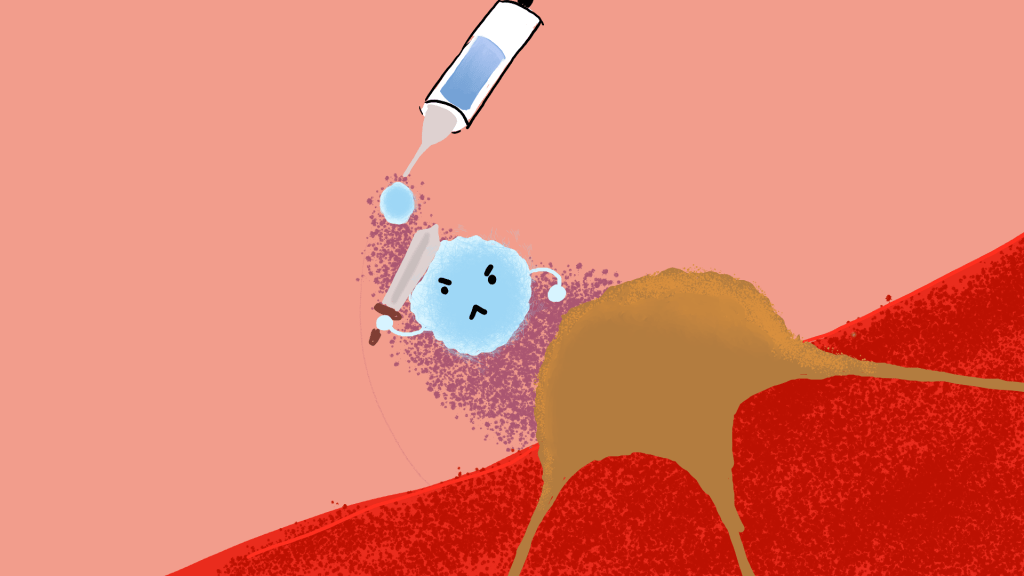

In general, cancer cells are particularly tricky to target because they have evolved or undergone genetic changes to make them less visible to the immune system. This may include proteins on their cell surfaces that disable immune cells or deceive them into thinking they are healthy cells, altering DNA packaging to evade detection of certain genes, and inducing the exhaustion of T-cells, a type of white blood cell. Various types of immunotherapy have been developed to counteract such strategies used by cancer cells. These include immune checkpoint inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and T-cell therapy. Checkpoint inhibitors are drugs that block immune checkpoints, which normally control the immune response rate of attacking cells so that the immune system can respond more strongly to cancer cells. Monoclonal antibodies are laboratory-made antibodies that are designed to bind to very specific targets on cancer cells. T-cell or adoptive therapy utilizes immune cells taken from a tumor and genetically engineers them to enhance their ability to recognize, bind to, and kill cancer cells. Essentially, all of these immunotherapy techniques interact with or manipulate the immune system in some sort of way to increase its chances of targeting cancer cells.

Administering immunotherapy can be done orally, intravenously, topically, or intravesically. It may be given alone or combined with other treatment methods like chemotherapy. Fortunately, immunotherapy has the benefit of having fewer and more well-tolerated side effects than other cancer treatments. As with many drugs, these side effects can include soreness, dizziness, fatigue, diarrhea, rashes, nausea, changes in blood pressure, weight fluctuations, and other physical inconveniences. In addition, immunotherapy can trigger immune responses strong enough to attack healthy cells, resulting in some cases involving organ inflammation or severe allergic reactions, though such cases are rare. Overall, the severity and amount of side effects experienced depends on a patient’s health pre-treatment, their type of cancer and its advancement stage, and the type and dose of immunotherapy received.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved immunotherapy for treating several types of cancers, including bladder, head and neck, esophageal, lung, and renal cell cancer. Immunotherapy has especially worked on melanoma, even going so far as to increase the survival rate of advanced melanoma from 5% to 50%. The reason for the success of immunotherapy in treating melanoma, and potentially other types of cancer, is that even if the cancer cells have many mutations, the immune system retains the ability to respond as those cells are still detected as foreign invaders. Immunotherapy simply enhances our body’s ability to fight off cancer, and current research seeks to improve upon this promising method.

References:

“Immunotherapy for Cancer.” Immunotherapy for Cancer – NCI, http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/immunotherapy.

Katella, Kathy, and Jeremy Ledger. “How Immunotherapy Can Treat Cancer and Other Diseases: 8 Things to Know.” Yale Medicine, Yale Medicine, 10 May 2024, http://www.yalemedicine.org/news/how-immunotherapy-can-treat-cancer-and-autoimmune-diseases.

Kim, Seong Keun, and Sun Wook Cho. “The evasion mechanisms of cancer immunity and drug intervention in the tumor microenvironment.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 13, 24 May 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.868695.

Leave a comment