Written by Kirsten Batitay | Art by Charlene Cheng

For many people, standing would not count as a grueling task, much less one to bat an eye at. However, those with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) face a different reality. A blood circulation disorder affecting around 1-3 million Americans, POTS is characterized by two factors: a specific group of symptoms experienced frequently when one stands upright and a considerable heart rate increase measured during the first ten minutes of standing–at least 30 beats per minute in adults and 40 beats per minute in young adults.

There are three subtypes of POTS to consider: neuropathic, hyperadrenergic, and hypovolemic. The first is when the “peripheral denervation (loss of nerve supply) leads to poor blood vessel muscles,” the second is when one’s sympathetic nervous system is overactive, and the last is when one has low blood volume. To understand these subtypes, we should first understand how POTS works.

Normally, when we stand, gravity pulls blood into the lower half of our body. While this might cause lightheadedness, our bodies counteract it when our leg muscles help bring blood back to the heart, and the autonomic nervous system stimulates our bodies to release epinephrine and norepinephrine, hormones that usually cause the heart to beat with more force and speed. The latter hormone also causes our blood vessels to constrict. For people with POTS, though, the blood vessels don’t normally respond to the hormone’s signal to tighten, but the two hormones still increase the heart rate, accounting for the symptoms that they experience.

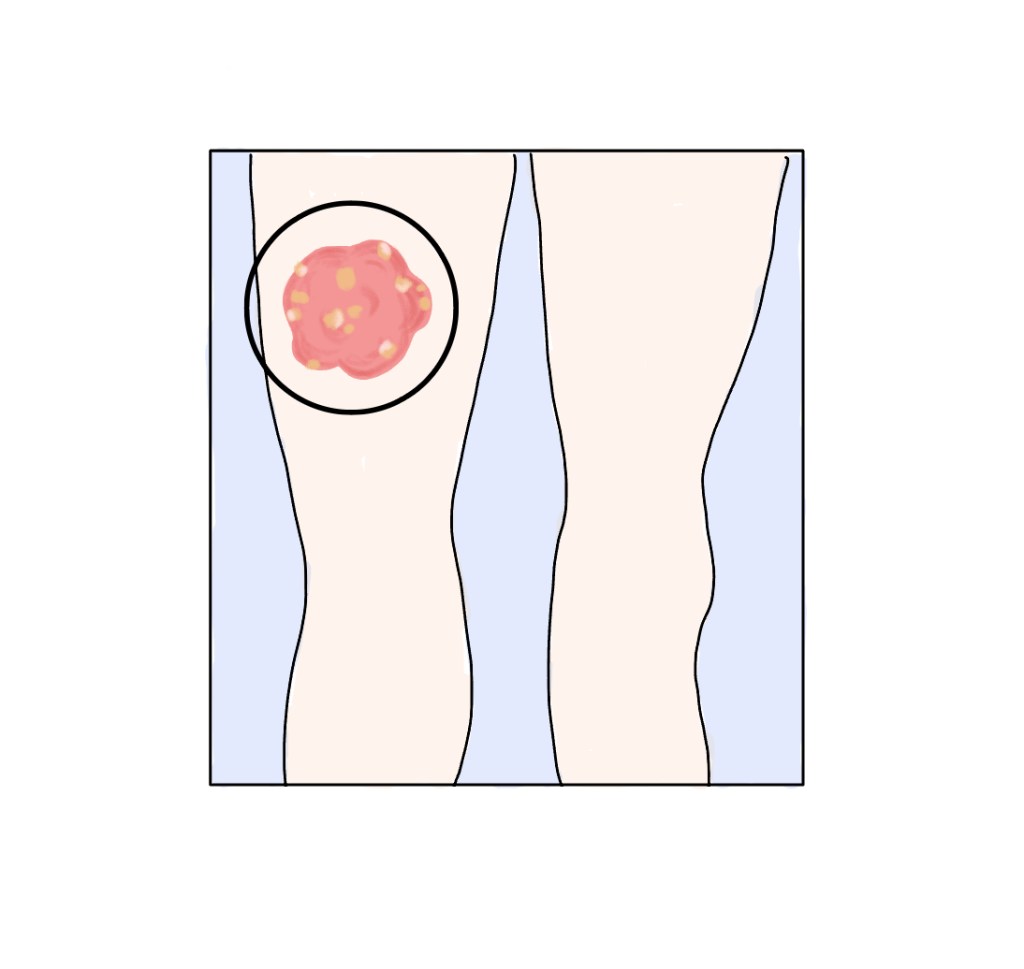

Such symptoms include severe or prolonged fatigue, brain fog (difficulty focusing and thinking), lightheadedness when sitting or standing for long periods of time that may be accompanied by fainting, intolerance of exercising, and heart palpitations, to name a few. These symptoms usually worsen in warm environments, situations when an individual has to stand often, and if they have not had sufficient fluid and salt intake.

Although scientists have yet to identify a single gene associated with POTS, the disorder may begin after a viral illness, surgery, or other health events. Despite there being no confirmed causes for POTS, there are certainly more reliable methods of diagnosis. These include physical examinations, blood tests, and either a ten-minute standing test or a tilt table test. A tilt table test is performed by having an individual lie down on a flat table and then raising it to an almost upright position.

The treatment of POTS combines factors of one’s diet, exercise, and medication. When it comes to diet, those with POTS are to drink 2-2 ½ liters of fluids per day, preferably water, and increase their salt intake to help retain water in the bloodstream so that more blood can reach the heart and brain. In terms of exercise, physical therapy can be helpful for some people with POTS, but the intolerance of exercise can be addressed by slowly increasing tolerance. Lastly, the FDA has yet to approve any medication for POTS treatment, but some can be prescribed off-label by healthcare providers to help with specific symptoms. These medications include fludrocortisone, beta-blockers, and midodrine.

Works Cited:

Cleveland Clinic Staff. “Pots: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 9 Feb. 2025, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16560-postural-orthostatic-tachycardia-syndrome-pots.

Hopkins Medicine Staff. “Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS).” Johns Hopkins Medicine, 21 Dec. 2022, http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/postural-orthostatic-tachycardia-syndrome-pots.

Leave a comment