Written by Farah Yasmin binti Firdaus Suffian | Art by Farah Yasmin binti Firdaus Suffian

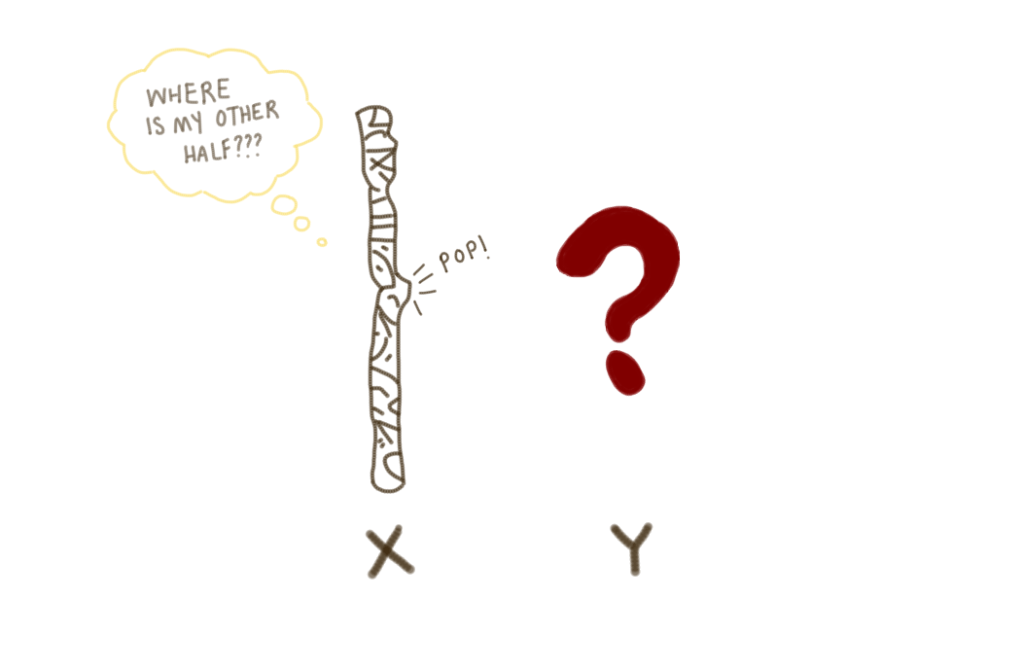

Turner syndrome (TS), a genetic condition affecting approximately 1 in 2000 girls, occurs when one X chromosome is missing or structurally altered. Unlike other chromosomal conditions, such as Down syndrome, the risk is not linked to maternal age. While much attention is placed on its medical aspects–from short stature to ovarian insufficiency–the associated social and emotional challenges faced by those with TS are often overlooked, creating invisible barriers that extend far beyond physical symptoms.

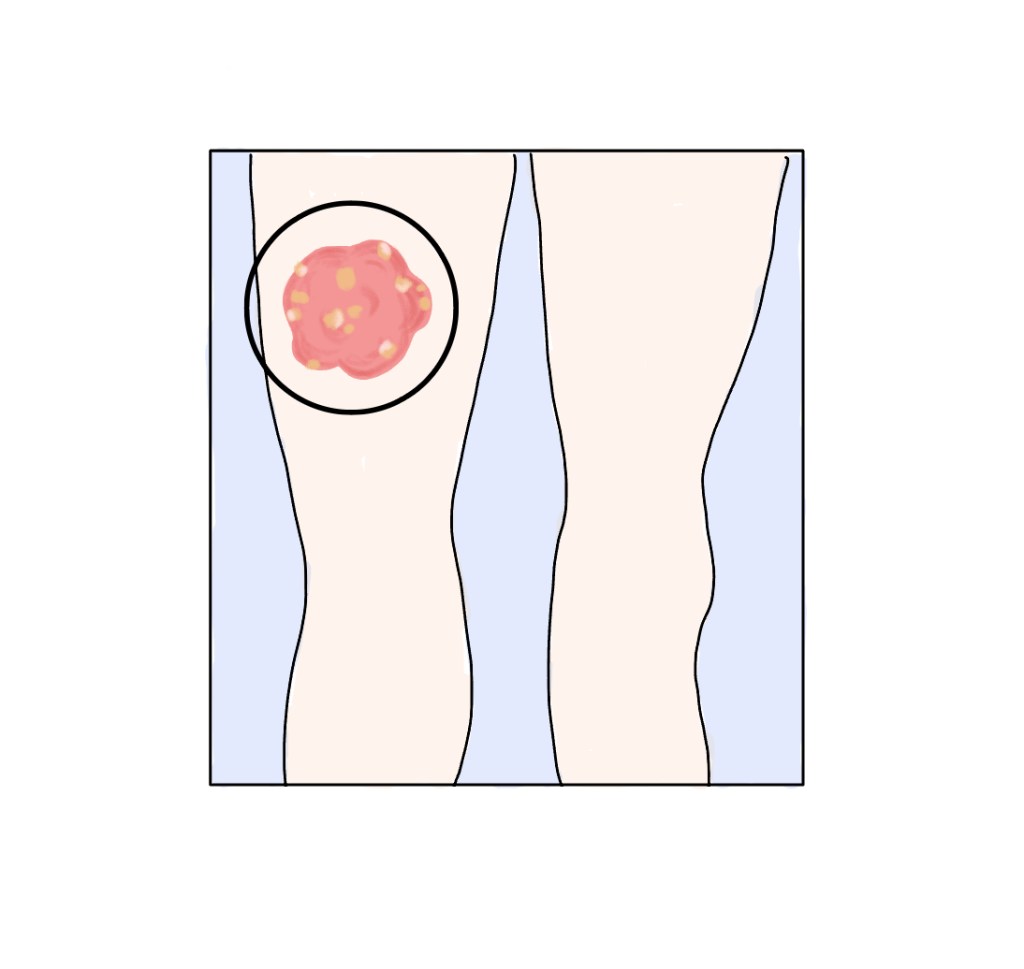

TS stems from various genetic abnormalities, most commonly the complete absence of one X chromosome (monosomy X) or a mosaic pattern when some cells have two X chromosomes while others have one. Structural changes to the X chromosome or rare cases involving Y chromosome material can also occur, which increases the risk of gonadoblastoma, a rare tumour found in the gonads (testes or ovaries). These genetic variations lead to a wide spectrum of physical manifestations. Girls with TS typically experience normal growth for their first three years before slowing down around age four. As they approach puberty, they will usually miss the typical adolescent growth spurt even with estrogen hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Distinctive physical features like a webbed neck, broad chest, upward-turning nails, and swelling of hands and feet often appear in infancy, while short stature, high-arched palate, and outward-turned elbows become noticeable in childhood. As they age, most individuals will experience having a short stature and ovarian insufficiency, leading to absent or incomplete puberty, infertility, and early menopause without hormone therapy. Other possible features include a high-arched palate, skeletal differences (e.g., outward-turned elbows), and cardiovascular complications. While some symptoms are apparent early, others–like learning difficulties or hormonal deficiencies–may develop gradually.

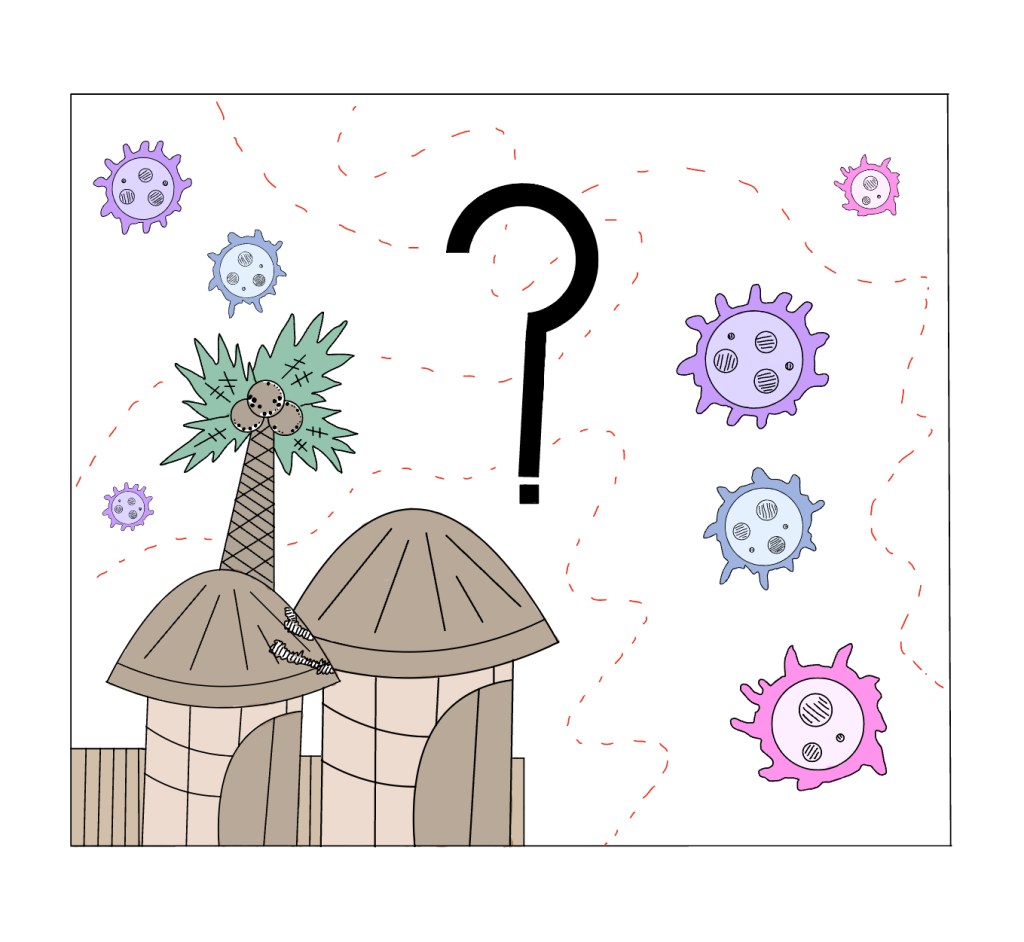

Diagnosis can occur prenatally through cell-free DNA screening (the mother’s blood is taken to detect chromosomal abnormalities, followed by confirmatory testing, if needed) or procedures like chorionic villus sampling (week 11-14 of pregnancy), amniocentesis (week 14 of pregnancy), or postnatally via blood tests or other tissue samples (e.g., cheek swab, skin biopsy). Early diagnosis is crucial, but it is often delayed in milder cases until growth delays or ovarian insufficiency become apparent.

Treatment for TS is tailored to each individual’s needs, with care coordinated by specialists including cardiologists, endocrinologists, and otolaryngologists. A primary focus is optimising growth–daily growth hormone injections begin in early childhood to maximise height potential before puberty. Around ages 11-12, estrogen therapy is introduced to trigger puberty, support breast and uterine development, and strengthen bones, often continuing until menopause to maintain sexual characteristics and bone density. Comprehensive care includes regular heart monitoring, hearing and vision support, thyroid checks, and fertility counselling. While infertility is common, options like egg donation offer some women the possibility of pregnancy.

The health implications of TS are extensive, including cardiovascular defects, hearing and vision problems, kidney abnormalities, autoimmune disorders like hypothyroidism and celiac disease, skeletal issues such as scoliosis and osteoporosis, and specific learning challenges, particularly in spatial reasoning and mathematics. These medical conditions require ongoing specialised care from specialists, with treatments including growth hormone therapy to maximise height potential and estrogen replacement to induce puberty and maintain bone health. However, the most profound challenges often lie in the social and emotional realm. The constant medical interventions, from daily hormone injections to frequent monitoring, reinforce feelings of being different in a world that values conformity. Learning differences are frequently misinterpreted as a lack of intelligence rather than being attributed to neurological aspects of TS. Perhaps most painfully, the near-universal infertility carries deep emotional weight in cultures where womanhood is closely tied to motherhood, creating feelings of inadequacy and isolation despite options like egg donation. This combination of visible differences, health challenges, and societal misconceptions creates layers of stigma that medical treatments alone cannot address.

Turner syndrome extends far beyond its medical complexities–it is a lifelong journey marked by both visible and invisible challenges. While treatments can address physical symptoms, the social stigma, emotional burdens, and societal misconceptions require equal attention. By fostering greater awareness, challenging stereotypes, and providing holistic support, we can create a world where individuals with TS are valued for their resilience rather than defined by their differences. True progress lies not just in medical advances but in building a more inclusive society that embraces all aspects of diversity.

Works cited:

- Kikkeri, NS., Nagalli S. Turner Syndrome. National Library of Medicine. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated 2023 Aug 8. Accessed 2025 Apr 8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554621/

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Turner Syndrome. Mayo Clinic [Internet]. 2022 Feb 11. Accessed 2025 Apr 8. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/turner-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20360782

- National Health Service. Turner syndrome: Overview. 2021 July 7. Accessed 2025 Apr 8. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/turner-syndrome/

- Khan N., Farooqui A., Ishrat R. Turner Syndrome Where are we? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024 Aug 28. [cited 2025 Apr 8]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-024-03337-0

Leave a comment